Post by Admin on Oct 30, 2022 21:28:54 GMT

Composite photo

Greeks, Cypriots and Neolithic Mediterranean Farmers Spread Agriculture to Scandinavia

Source: Kathimerini, 28.04.2012 (Translated from Greek and referenced by A.M.)

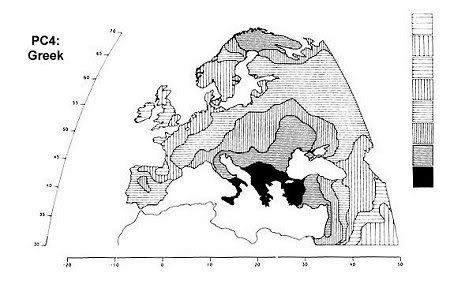

Agriculture spread to Europe thousand of years ago from the South to the distant North, with successive steps, according to the Swedish-danish scientific research. The study analysed the DNA of the four [inhabitants of Scandinavia] of the Neolithic period and found that they had many more genes in common with today’s Southern Europeans, as the Greeks, Cypriots the inhabitants of Sardinia, than with any other European people.

The researchers of the Universities of Upsala, Stockholm, and Copenhagen, having at their head Pontus Skoglund and Mattias Jakobsson who published the study in the American journal “Science” according to the French Agency and “Nature”, analysed using new developed techniques, the genetic material that they took from the skeletons of one farmer and three hunter-gatherers, who had been discovered in Sweden and are dated to about 5000 years from the present. The two distinct civilisations, one agricultural and one of hunter-gatherers, coexisted for about 1000 years at a distance of about 400 km, the first in the Swedish hinterland and the second on the island of Gotland, south of Stockholm.

By comparing the DNA of these people of the Stone Age with the DNA of modern populations of Europe, the team found that, from a genetic point of view, the hunter-gatherers were less developed and had a greater relation with the Northern populations – especially the inhabitants of today’s Finland, while the farmer had a very close genetic relationship with today’s Mediterranean populations, especially Cypriots and Greeks.

This discovery by the Scandinavian scientists shows that the ancient farmers transported their agricultural knowledge and technique from the South to the rest of Europe, up to the frozen North, where they finally mingled with the indigenous populations, while teaching them how to grow their food rather than hunt and gather fruits.

As Skoglund stated, the genetic findings reveal that agriculture spread to the whole of Europe by people who live in the Mediterranean and this happened through migratory waves and not just by the cultural transmission of agricultural knowledge from mouth to mouth. “If farming had spread only as a cultural process, we would not find a farmer in the North who has such a genetic relation to the Southern populations”, declared the Swedish scientist.

The Scandinavian research illuminates a longstanding dispute among scientists concerning the way that farming reached Europe from the Middle East, where it appeared approximately 11000 years ago. At about 3000 B.C. farming had already spread to the greater part of Europe. The basic dispute concerns the way that the transition from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle to that of farmer, and whether farming spread through the migration of farmers or if just ideas and the agricultural know-how spread slowly from civilisation to civilisation. The new study gives more weight to the first view, confirming previous DNA analyses, which had found similar indications about the migration of people themselves from the Mediterranean, who brought their farming knowledge with them.

Furthermore earlier this year scientists published almost all of the genome of “Ötzi”, the Neolotic mummy that was discovered in the Alp in 1991. In this case as well, the genetic analysis shows a very possible Mediterranean origin.

Abstract from Science, 27.04.2012: Origins and Genetic Legacy of Neolithic Farmers and Hunter-Gatherers in Europe

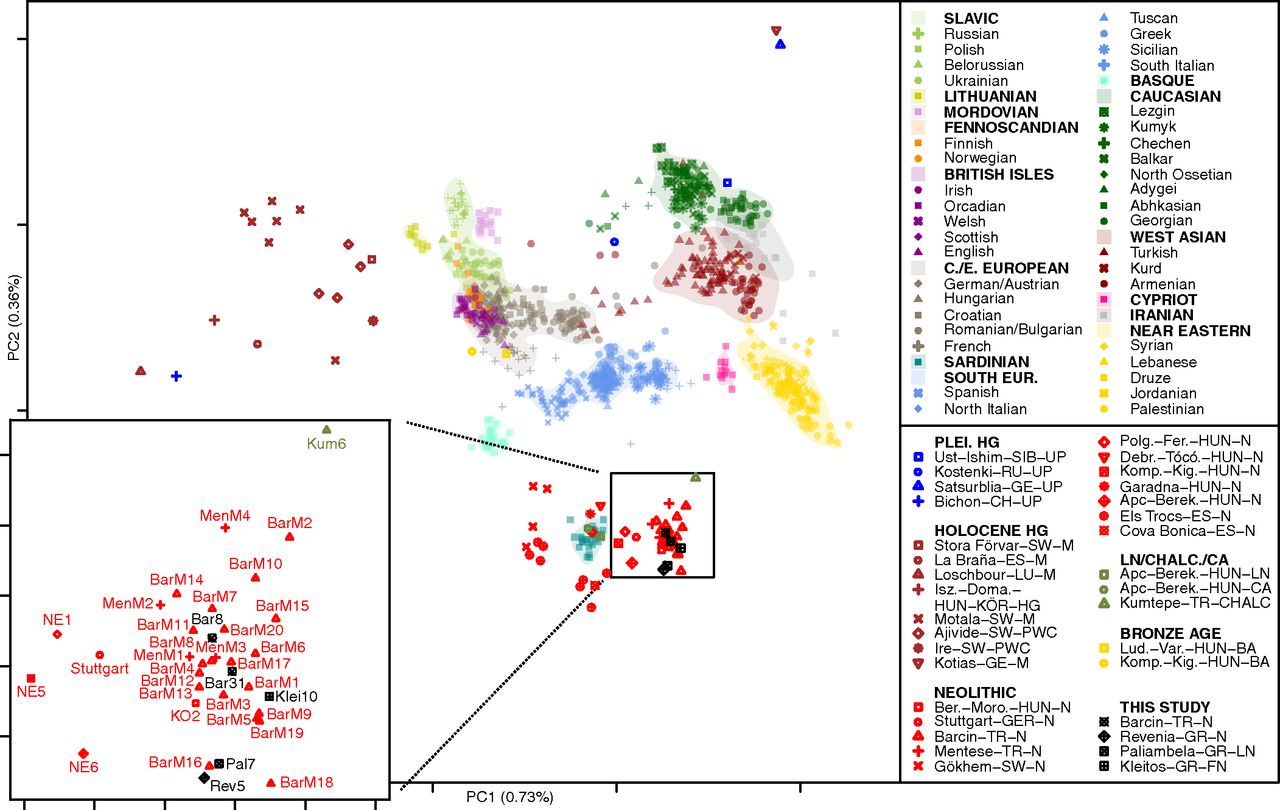

The farming way of life originated in the Near East some 11,000 years ago and had reached most of the European continent 5000 years later. However, the impact of the agricultural revolution on demography and patterns of genomic variation in Europe remains unknown. We obtained 249 million base pairs of genomic DNA from ~5000-year-old remains of three hunter-gatherers and one farmer excavated in Scandinavia and find that the farmer is genetically most similar to extant southern Europeans, contrasting sharply to the hunter-gatherers, whose distinct genetic signature is most similar to that of extant northern Europeans. Our results suggest that migration from southern Europe catalyzed the spread of agriculture and that admixture in the wake of this expansion eventually shaped the genomic landscape of modern-day Europe.

archaeologymatters2.blogspot.com/2012/04/greeks-cypriots-and-neolithic.html

Hunter-gatherer skeletons excavated in Sweden, including these remains of a young woman, have provided genetic evidence that these groups mated with nearby farmers who arrived from southern Europe around 5,000 years ago. Credit: Goran Burenhult.

Ancient Swedish farmer came from the Mediterranean

Five-thousand-year-old DNA gives insight into the spread of agriculture across Europe.

Geneticists analysing DNA from Neolithic burial sites in Sweden have made a surprising discovery. The genetic make-up of one individual — a female farmer known as Gök4 — bears a startling similarity to that of modern-day Mediterraneans. And the woman's genome provides clues as to how agriculture spread across Europe.

“The farmer is most genetically similar to people living in Cyprus and Sardinia today,” says Pontus Skoglund, an evolutionary geneticist at Uppsala University in Sweden and the lead author of the study, which is published today in Science1.

Gök4's 5,000-year-old remains were found in Gökhem parish, southern Sweden. The discovery of her ancestry feeds into a long-running debate over the transition from foraging to farming in prehistoric Europe, a process that archaeologists refer to as Neolithization.

It is well established that agriculture had its origins in the near east, but there are still plenty of questions about how it spread. In particular, did resident hunter-gatherers independently hit on the idea of agriculture, learn about it through word of mouth or become introduced to it through the movement of people with farming know-how from south to north?

Efforts to address this question by sequencing the mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosomes of modern Europeans have proved inconclusive2. In recent years, researchers have also been studying mitochondrial DNA from prehistoric specimens3,4,5. They have found tentative support for the idea that agriculture spread across Europe through migration rather than word of mouth, but their conclusions are based on analyses of only a single piece of DNA from each specimen, so they are open to question.

To get a more reliable snapshot, Skoglund and his colleagues sequenced almost 250 million base pairs from the skeletal remains of four individuals: Gök4 and three hunter-gatherers from around the same period, whose burial sites were located less than 400 kilometres from Västergötland, on the island of Gotland.

The hunter-gatherers show the greatest similarity to modern-day Finns, says Skoglund. “It was a surprise that the farmer and hunter-gatherers were so different. Scandinavia was clearly home to people of very different genetic backgrounds even 5,000 years ago,” he says.

Farming on the move

The result is strong evidence for the migration hypothesis. "If farming had spread solely as a cultural process, we would not expect to see a farmer in the north with such genetic affinity to southern populations,” says Skoglund.

But Wolfgang Haak, a human palaeobiologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia and a co-author of some of the mitochondrial studies, says that “one farmer from Scandinavia is certainly not enough to explain the spread of farming in places like Spain or Bulgaria and we definitely need more farmers from other parts of Europe”.

Another ancient DNA study, published this week in PLoS One6, compares the mitochondrial DNA of Neolithic farmers and hunter-gatherers in northern Spain. The genetic variation amongst the farmers indicates that there was a complex pattern of settlement, with waves of colonization bringing small and different Neolithic groups into the region.

“Given the genetic evidence from studies of both modern-day and ancient DNA, I am convinced that farmers expanded in many different ways and under many different demographic scenarios,” says Haak. But Skoglund's study adds “an important piece to the big puzzle” of how farming became commonplace across Europe, Haak adds.

It is also an exciting indication of the direction the field is taking, he says. Earlier this year, researchers published a near-complete genomic sequence from Ötzi, the Neolithic mummy found in ice in the Alps in 1991, which revealed that he had also probably come from Mediterranean stock7. “The technical advances in the genomic era now provide us with the necessary tools to tackle the different modes of the Neolithization in every corner of Europe with much higher precision,” says Haak.

There is also the tantalizing prospect that as understanding of the genetic basis of behaviour improves, it might be possible to comb fragments of ancient DNA for signs of behavioural differences between prehistoric populations. “In the future we might know a few genes that affect behaviour and we could go back and look into the hunter gatherers and see what variants of those genes are present,” says Mattias Jakobsson, a population geneticist at the University of Uppsala and a co-author of the Science paper. “But that’s not going to happen in the next couple of weeks at least.”

www.nature.com/articles/nature.2012.10541

Ancient DNA from Neolithic Sweden (Skoglund et al. 2012)

dienekes.blogspot.com/2012/04/ancient-dna-from-neolithic-sweden.html

Early farmers from across Europe directly descended from Neolithic Aegeans

www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1523951113

Neolithic Aegean genomes

dienekes.blogspot.com/2016/06/neolithic-aegean-genomes.html

ADMIXTURES

Mediterranean admixture

15-20% in Scandinavia

Neolithic farmer admixture

30-40% in South Scandinavia