Post by Admin on Nov 26, 2022 22:19:41 GMT

...hypothesis

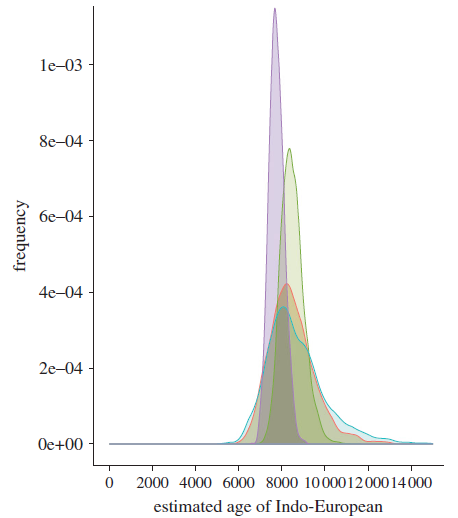

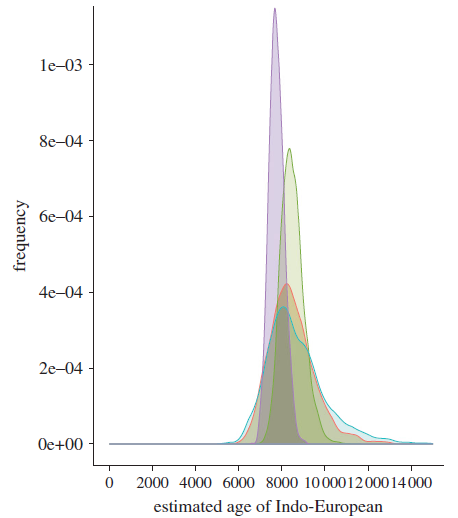

The recognition that Bayesian phylogenetic methods, first developed in biology, could also be applied to the evolution of languages, has been one of the most exciting developments over the last decade.

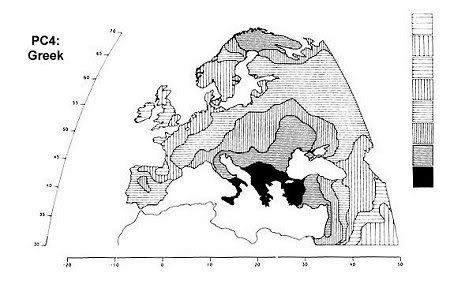

This realization, is due in a great part to Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson (henceforth G&A) and their influent 2003 Nature article, in which they argued that a robust estimate, consistent with the Anatolian hypothesis of Indo-European origins (left), could be inferred from lexicaldata.

The G&A was initially met with skepticism because it was conflated with glottochronology, a now controversial method of inferring language time depth based on rates of retention of cognates. Glottochronology tried to apply a regular law to linguistic change, a notoriously irregular process. As the authors of the current paper note: glottochronological calculations with considerable scepticism. The most fundamental obstacle encountered by glottochronology is the fact that languages, just like genes, often do not evolve at a constant rate.

In their classic critique of glottochronology, Bergsland & Vogt [12] compared present-day languages with their archaic forms. They found considerable evidence of rate variation between languages. For example, Icelandic and Norwegian were compared with their common ancestor, Old Norse, spoken roughly 1000 years ago. Norwegian has retained 81 per cent of the vocabulary of Old Norse, correctly suggesting an age of approximately 1000 years. However, Icelandic has retained over 95 per cent of the Old Norse vocabulary, falsely suggesting that Icelandic split from Old Norse less than 200 years ago.

The critics largely ignored the fact that G&A's method avoided the problems of glottochronology, such as the questionable assumption of a constant rate of evolutionary change: instead, the G&A method exploited multiple known calibration points (e.g., the breakup of Romance languages in Late Antiquity) and did not need such a strict and unrealistic assumption.

The authors of the current paper bemoan the strange reversal of fortunes of computational methods in biology and linguistics. Whereas the attempt to estimate dates from variation has a longer pedigree in linguistics than in biology (and I would add that it was even older than the radiocarbon revolution in archaeology), computational methods have won the day in biology, and been abandoned by linguists:

It is ironic that over the past half-century, computational methods in historical linguistics have fallen out of favour while in evolutionary biology computational methods have blossomed. Rather than giving up and saying, ‘we don’t do dates’, computational biologists have developed methods that can accurately estimate phylogenetic trees and divergence dates even when there is considerable lineage-specific rate heterogeneity.

Much of the criticism against G&A stemmed from the received "knowledge" that Indo-European could not have been as old as the Neolithic spread from Anatolia to Europe. And, yet, if you ask linguists why they are so sure that this is the case, you will mostly get either (i) a non-quantitative opinion (i.e., an ex cathedra guess, since linguists "don't do dates"), or (ii) a redirect to archaeology. Ask archaeologists who ascribe to the same opinion, and you will either get a redirect to "linguists", completing the loop, or an inexplicable belief in the ability of Chalcolithic pastoralists from the Eurasian steppes of effecting almost total linguistic replacement over a huge area from the Atlantic to India, despite:

meagre evidence for their actual presence outside the steppes and a few bordering areas, such as the Danubian region, and

a total lack of knowledge of what languages early steppe pastoralists spoke, assuming that because Scythians spoke (most likely) an Iranic language 2-3 thousand years later, so must have the early steppe populations

What followed the publication of the 2003 article was a remarkable back-and-forth between G&A and their critics, in which one by one the technical objections to their discovery was addressed, and computational linguistic techniques reached maturity by being applied in numerous different ways and on different datasets for the problem of not only Indo-European, and on different language families, such as Semitic, Austronesian, Melanesian, the languages of the Sahul, and Arawak.

The new paper is a nice summary of what has transpired over the last eight years. G&A together with Simon Greenhill detail how one by one the skeptics' arguments have been addressed:

Both the Dyen et al. dataset mostly of modern Indo-European languages as well as an independent one by Ringe et al. on mostly ancient ones gave similar results

Binary vs. multi-state coding of cognate sets gave similar results

By removing calibration points they estimated the age of nodes of known age, coming up with results close to the truth and, in any case, not systematically older

An application of Dollo's Law on both the Ringe et al. and Dyen et al. data, i.e., higher rate of cognate gain than cognate loss did not affect the time depth of the estimate

Removing some calibration points, or cognates dubbed as dubious in the data, or of limiting the analysis to the most stable ones didn't affect the results, and sometimes made them appear older

I've often said that linguistics is dangerous territory, as a handful of people are probably proficient in all the languages involved, which includes not only several IE sub-families, but also Semitic, Finno-Ugrian, and NE/S Caucasian. Nonetheless, I can't help but notice that G&A and their colleagues have done an exceptional job of addressing objections to their work in a replicable and quantitative manner.

Archaeological and Genetic evidence

The Anatolian hypothesis has been challenged on non-linguistic as well as linguistic grounds. In terms of archaeology, there is a school of thought that favored static models of cultural change and was allergic to migration. However, recent work on both the craniometry and the DNA of ancient farming communities in Europe in comparison to the Mesolithic population is supportive of a population influx.

Surprisingly, this influx does not seem to be a good match to either static models or the classical demic diffusion hypothesis, in which farmers advance in small steps, gradually intermingling with foragers before moving on further away from their region of origin. Instead, early farming communities in LBK largely avoided the foragers and vice versa, an idea that is borne out by the surprisingly large measurable genetic differences between the two populations.

Hence, there is clear evidence of a population transfer during the onset of the Neolithic; once fashionable ideas like: "Mesolithic people received grains and pots, but not people and languages from West Asia" are not valid. We cannot be sure what languages the European proto-farmers spoke, but, their path is consistent with the Anatolian hypothesis, and provides a parsimonious explanation for the oldest split between Anatolian languages and Indo-European.

Conclusion

The Anatolian hypothesis of Indo-European origins is very much alive, and, in my opinion, still the best explanation for the fact that people from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean and the outskirts of China speak/spoke languages stemming from a common ancestor.

dienekes.blogspot.com/2011/04/indo-european-origins-neolithic.html

The recognition that Bayesian phylogenetic methods, first developed in biology, could also be applied to the evolution of languages, has been one of the most exciting developments over the last decade.

This realization, is due in a great part to Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson (henceforth G&A) and their influent 2003 Nature article, in which they argued that a robust estimate, consistent with the Anatolian hypothesis of Indo-European origins (left), could be inferred from lexicaldata.

The G&A was initially met with skepticism because it was conflated with glottochronology, a now controversial method of inferring language time depth based on rates of retention of cognates. Glottochronology tried to apply a regular law to linguistic change, a notoriously irregular process. As the authors of the current paper note: glottochronological calculations with considerable scepticism. The most fundamental obstacle encountered by glottochronology is the fact that languages, just like genes, often do not evolve at a constant rate.

In their classic critique of glottochronology, Bergsland & Vogt [12] compared present-day languages with their archaic forms. They found considerable evidence of rate variation between languages. For example, Icelandic and Norwegian were compared with their common ancestor, Old Norse, spoken roughly 1000 years ago. Norwegian has retained 81 per cent of the vocabulary of Old Norse, correctly suggesting an age of approximately 1000 years. However, Icelandic has retained over 95 per cent of the Old Norse vocabulary, falsely suggesting that Icelandic split from Old Norse less than 200 years ago.

The critics largely ignored the fact that G&A's method avoided the problems of glottochronology, such as the questionable assumption of a constant rate of evolutionary change: instead, the G&A method exploited multiple known calibration points (e.g., the breakup of Romance languages in Late Antiquity) and did not need such a strict and unrealistic assumption.

The authors of the current paper bemoan the strange reversal of fortunes of computational methods in biology and linguistics. Whereas the attempt to estimate dates from variation has a longer pedigree in linguistics than in biology (and I would add that it was even older than the radiocarbon revolution in archaeology), computational methods have won the day in biology, and been abandoned by linguists:

It is ironic that over the past half-century, computational methods in historical linguistics have fallen out of favour while in evolutionary biology computational methods have blossomed. Rather than giving up and saying, ‘we don’t do dates’, computational biologists have developed methods that can accurately estimate phylogenetic trees and divergence dates even when there is considerable lineage-specific rate heterogeneity.

Much of the criticism against G&A stemmed from the received "knowledge" that Indo-European could not have been as old as the Neolithic spread from Anatolia to Europe. And, yet, if you ask linguists why they are so sure that this is the case, you will mostly get either (i) a non-quantitative opinion (i.e., an ex cathedra guess, since linguists "don't do dates"), or (ii) a redirect to archaeology. Ask archaeologists who ascribe to the same opinion, and you will either get a redirect to "linguists", completing the loop, or an inexplicable belief in the ability of Chalcolithic pastoralists from the Eurasian steppes of effecting almost total linguistic replacement over a huge area from the Atlantic to India, despite:

meagre evidence for their actual presence outside the steppes and a few bordering areas, such as the Danubian region, and

a total lack of knowledge of what languages early steppe pastoralists spoke, assuming that because Scythians spoke (most likely) an Iranic language 2-3 thousand years later, so must have the early steppe populations

What followed the publication of the 2003 article was a remarkable back-and-forth between G&A and their critics, in which one by one the technical objections to their discovery was addressed, and computational linguistic techniques reached maturity by being applied in numerous different ways and on different datasets for the problem of not only Indo-European, and on different language families, such as Semitic, Austronesian, Melanesian, the languages of the Sahul, and Arawak.

The new paper is a nice summary of what has transpired over the last eight years. G&A together with Simon Greenhill detail how one by one the skeptics' arguments have been addressed:

Both the Dyen et al. dataset mostly of modern Indo-European languages as well as an independent one by Ringe et al. on mostly ancient ones gave similar results

Binary vs. multi-state coding of cognate sets gave similar results

By removing calibration points they estimated the age of nodes of known age, coming up with results close to the truth and, in any case, not systematically older

An application of Dollo's Law on both the Ringe et al. and Dyen et al. data, i.e., higher rate of cognate gain than cognate loss did not affect the time depth of the estimate

Removing some calibration points, or cognates dubbed as dubious in the data, or of limiting the analysis to the most stable ones didn't affect the results, and sometimes made them appear older

I've often said that linguistics is dangerous territory, as a handful of people are probably proficient in all the languages involved, which includes not only several IE sub-families, but also Semitic, Finno-Ugrian, and NE/S Caucasian. Nonetheless, I can't help but notice that G&A and their colleagues have done an exceptional job of addressing objections to their work in a replicable and quantitative manner.

Archaeological and Genetic evidence

The Anatolian hypothesis has been challenged on non-linguistic as well as linguistic grounds. In terms of archaeology, there is a school of thought that favored static models of cultural change and was allergic to migration. However, recent work on both the craniometry and the DNA of ancient farming communities in Europe in comparison to the Mesolithic population is supportive of a population influx.

Surprisingly, this influx does not seem to be a good match to either static models or the classical demic diffusion hypothesis, in which farmers advance in small steps, gradually intermingling with foragers before moving on further away from their region of origin. Instead, early farming communities in LBK largely avoided the foragers and vice versa, an idea that is borne out by the surprisingly large measurable genetic differences between the two populations.

Hence, there is clear evidence of a population transfer during the onset of the Neolithic; once fashionable ideas like: "Mesolithic people received grains and pots, but not people and languages from West Asia" are not valid. We cannot be sure what languages the European proto-farmers spoke, but, their path is consistent with the Anatolian hypothesis, and provides a parsimonious explanation for the oldest split between Anatolian languages and Indo-European.

Conclusion

The Anatolian hypothesis of Indo-European origins is very much alive, and, in my opinion, still the best explanation for the fact that people from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean and the outskirts of China speak/spoke languages stemming from a common ancestor.

dienekes.blogspot.com/2011/04/indo-european-origins-neolithic.html