Post by Admin on Nov 25, 2022 23:06:03 GMT

THE GENETIC COMPOSITION OF THE INHABITANTS OF GREECE by Constantinos Triantaphyllidis

Professor of Genetics

School of Biology Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

THESSALONIKI 1993

Introduction to the speech «The genetic composition of the inhabitans of Greece» by Dr Penelope MinasidouMavridou, President of the Medical Women Association of North Greece.

When a few years ago, the French historian Dyrosel wrote in one of his books and commented in interviews that «the Greeks come from the Turks and that the entry of Greece into the European Community was a mistake» we were all deeply enraged by these unfounded and untrue historical remarks. Of course we all, not of the faculty of Biology, did not know that apart from historical data, we could also prove Dyrosel and some other so called friends wrong based on scientific research. We did not know that in the School of Biology of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the Professor of Genetics Mr C. Triantaphyllidis and his associates had a scientific publication about our genetic origin. When we read in the press the article-protest of Dr. C. Triantaphyllidis, which also referred to more publications from foreign Universities dealing with the same subject, like the one of Professor Piazza and associates from the University of Torine, we felt proud of this not only serious, but also valuable publication of our university and we as a Medical Women Association of North Greece, concluded that the results of this scientific research be known to all us Greeks and consequently to the whole world. Every Greek, wheever he may be, is interested in discovering his roots and this not in order to feel more Greek, of this he is certain, but to be able to refute not only historically but also scientifically antihellenic opinions of some people and others who have designs on our Greek heritage. The Medical Women Association of North Greece would like to thank Dr C. Triantaphyllidis who so readily answered our request that this speech be given and that he takes care of the publication of this leaflet which is a summary of the subject «The genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece» written in Greek and English to be sent all over Greece and even all around the world, so that everyone realises how Greek our genealogy is, genetically speaking as well. The Medical Women Association of North Greece owe a big thanks to the President of the Medical Association of Thessaloniki Dr N. Aggelidis, the General Secretary Dr G. Xatzedemos and the board who so eagerly cooperated in the organization of the speech which took place in the Chamber of Commerce on March 3rd 1993 and who were the granters of the capital for the first edition of the leaflet titled « The genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece». We would also like to thank the colleaque Dr C. Stasinopoulos, the Editor of the Journal of Medicine Galinos and Mr Pan. Papageorgiou, Manager Editor of the Journal, for the publication of the speech in the Journal and the republication of the leaflet so that it continues to be sent to all the Libraries of the World and to many Institutions.

The first inhabitants of Greece, the Prohellens, arrived in Greek territory at about 8.000 to 6.000 BC. Later, they developed in Crete and the Greek islands those marvellous civilizations which are known as Minoan and Cycladic. The Hellenes (= Greeks) arrived on the Greek mainland in succesive waves during the end of the Bronze Age (2.500 to 1.000 BC). Their arrival has been establisched through archaelogical excavations, linguistic records and literaly sources. The next three centuries (1.100-800 BC) saw an increase of Greece's population, while Hellenic(=Greek) civilization and culture were advanced. Meanwhile, important colonizing enterprises started, which spread the Hellenes futher afield from the Greek mainland. By the 8th century there were Hellenic settlements in modern Bulgaria and Rumania, on the coasts of the Black sea and of Asia Minor. The Greeks also colonized parts of Sicily and Southern Italy, which came to be known as Magna Graecia (Great Greece) and many points along the French, Spanish and North Africa coasts. This Early colonization was the beginning of a process of Hellenization of the indigenous populations. In the 4th century Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) extended greek colonization and civilization even further, to include much of Egypt and the Middle East and to reach even India. Colonization and hellenization continued for more than two hundred years and was maintained during the Roman imperial rule. During the Byzantine period Anatolia, with the major city in the interior of Cappadochia, was one of the most important regions with a Greek population outside of Greece itself. The study of the inhabitants of Hellas (= Greece) is usually based on historical, linguistic and archaeological records. This article aims to investigate the same subject from a different angle, since it is based on Biomediqal - genetical - data. It is worth mentioning that it was in Greece that the first study of blood group frequencies was ever made. It was carried out by Professor and Mrs Hirszfeld (1919) when they were working in Salonika during the First World War and had the opportunity of studying large numbers of soldiers frome different countries. Five hundred Greeks were included in their samples. Since then, and up to the present day, a number of investigators, mostly greeks, have studied the frequency of alleles of genes that code for blood groups, enzyme and protein polymorphisms, among the Greek people. Several authors have studied local or isolated Greek populations. This aricle is an attempt to present the genetic structure of the inhabitants of modern Greece, as well as the genetic composition of isolated Greek populations for which enough genetical data are available. These populations are the refugees from Asia Minor, the endogamic and nomadic populations of Sarakatsans and the Gypsies. The history of a language - its evolution - can be traced from the simiiiarities and differences of living languages and their literaly fossils. Such linguistic evidence can be used to trace the history and relationships of populations. In the same way, shared genes can be used to trace patterns of genetic relationships among human populations. Because of the above mentioned immigration of Greeks all over the Mediterranean region, it seems interesting to investigate the genetic relationships between the inhabitants of Greece and the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries as well as between the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries and the three major human reces*. Previously, the genetic relationships between the human populations were studied mainly by using morphological characters. In recent years, however, blood groups and other protein and enzyme polymorphism (1976) have been studied in human populations. The study of blood groups and other genetic polymorphisms for this type of work is more attractive from, say craniometric data, because of two reasons: their lack of environmental lability and their simple genetic determination. Today, for the same purpose, the scientists are studying the polymorphism of the mitochondrial and nuclear genetic meterial (DNA), as well as the differences in the order of nucleotides of particular segments of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.

* The data from population genetic studies support the notion that there are no human races, but only human populations. So, the term race, in this article, is used only for the convenience of presentation of the results.

A. The genetic relationship between the inhabitants of Greece and the inhabitants of other Mediterranean countries.

The Mediterranean region is divided into many countries. The population of this area is quite diverse consisting of people of different nationality, language and religion. Hence, it is worthwhile to determine the genetic relationships among the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries as well as the genetic distances between the inhabitants of 9 Mediterranean countries and the 3 major human races. For that purpose data on at least 16 genetic loci from nine Mediterranean countries were used (1,2). The genetic markers that were included were blood groups, ie ABO, MNSs, Rhesus, etc, protein loci: ACPH, AK, Hp, etc, from the following countries: France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Libya, Israel, Egypt, Algeria. We also decided to include Bulgaria in the study. The majority of the data for Caucasoids and Mongoloids were taken from US Caucasians and from Japanese, respectively. The data for Negroids were taken from Africans as well as from African Americans. Using the above mentioned data the genetic distances among the inhabitants of the nine Mediterranean countries were computed. Using these estimates, a dendrogram (Fig 1) has been constructed. The smallest genetic distances (or the greater genetic similarity) occur between French - Spaniards, Greeks - Italians, French - Italians and French - Greeks, whereas the greatest distances are between the Algerians and the inhabitants of the other Mediterranean countries. The populations of the North Mediterranean countries were clustered together, whereas this was not the case for South Mediterraneans. Thus one can conclude that the genetic distance of the inhabitants of Greece from the populations of other countries decreases in the following order: Italy, France and then Turkey. These findings therefore strongly contradict the suggestion of the French historian Z Dyrozel that the Greeks are descentants of Turks.

B. The genetic distances between the inhabitants of nine Mediterranean countries and the three major human races.

Anthropologically, the Mediterraneans belong to the Caucasoid group, although some Negroid and Mongoloig admixtures have to be taken into account. The genetic analysis demonstrates certain features of interest.

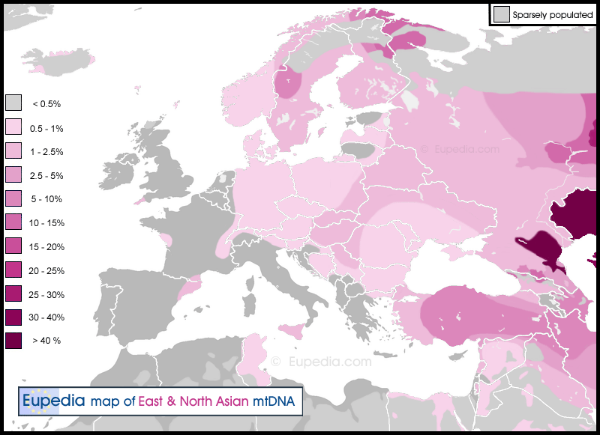

1. The genetic distance of the populations of North Mediterranean countries from Caucasoids decreases

from the East to the West.

2. The genetic distance from Mongoloids increases from the East to the West for the populations of North and South Mediterranean countries.

3. The genetic distances between Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Italians, Spaniards, French, Israelis and Caucasians are smaller than that between the inhabitants of each country and the Negroids.

4. Libyans and Egyptians are closer to Negroids than to Mongoloids and Algerians are closer to Negroids than to Caucasoids. This is probably caused by Negroid immigration into these countries.

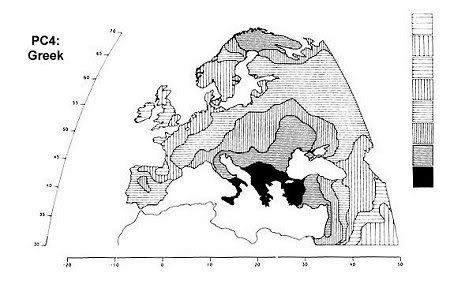

C. Comparison between the genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece and Italy.

Our results show, that the inhabitants of Greece and Italy are genetically very close. It is worth mentioning that Professor A Piazza et al (3) of the Dipartimento of Genetica of the University of Torino has reached the same conclusion. For the reconstruction of the genetic history of the inhabitants of Italy his Laboratory has used many genetic loci (blood groups and protein polymorphisms), as well as historic and linguistic records. By 400 BC the population of Italy was about 4 million people. The Greek colonies of Sicily alone accounted for 1,5 million .people, of which more than 10% (about 200.000) were of Greek origin. To these Greek inhabitants of Sicily another 100.000 Greek colonizers in the Italian peninsula, may be added so that before the Roman period, one in every 10-13 inhabitants of Italy was Greek. Even if these numbers must be taken with caution, their order of magnitude might give an explanation for the remarkable differentation of Magna Greacia (South Italy and Sicily) from the rest of the Italian mainland, as well as for the great genetic similarity of the Italian southern regions with the inhabitants of modern Greece. The loci used for such studies are mainly polymorphic. Thus, the calculated genetic distances tend to be an overestimate. Keeping this fact in mind, one can estimate the time since divergence between the Greeks, the Italians, the French and the Spaniards. These populations appear to have diverged from the Caucasoid line about 8.000 years ago or in the mesolithic period. This rough estimate based on evidence of molecular evolution aggrees quite well with suggestions based on anthropometric measurements and archaeological evidence that North Mediterranean populations migrated from a common root in Central Europe.

D. Comparison between the genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece and Bulgaria.

The genetic polymorphisms have been studied in only one other Balkan population, that of Bulgaria. Historically, the two populations differ considerably. The Greeks migrated to Southeastern Europe at about 1500 to 1100 BC. The Bulgarians, a Mongolic tribe migrated to what is today Bulgaria during the 8th century AD. There they were absorbed by local Slav populations. The estimated genetic distances between the inhabitants of Bulgaria and the four Mediterranean countries studied (Turkey, Greece, Italy and France) indicate that: The genetic composition of the inhabitants of Bulgaria is closer to that of the inhabitants first of Italy, next of Turkey, and then France, whereas the greatest genetic distance was found between the inhabitants of Greece and Bulgaria. The gene frequencies of five polymorphic systems (AK, PGM, ADA, ACPH, 6-PGD) in the Greek and Bulgarian populations were compared in 1975, by Stamatoyannopoulos et al (4) of the Division of Medical Genetics, University of Washington Seattle, USA. Only one system, AK, has similar frequencies. Thus, among the polymorphic systems so far compared, statistically significant differences were observed in four systems. Therefore, the distribution pattern of the gene frequencies differs considerably between the two populations. Furthermore, the pattern of gene frequencies in the Bulgarian population resembles to that of Asiatic populations. The existing data also sheds some light on the debate between Greek and Slavic historians regarding the ethnic origin of the population inhabiting Greek Macedonia. On the gene grequencies of seven polymorphic systems (AK, PGM, ADA, ACPH, 6-PGD, Hp and ABO) studied in the inhabitants of Greek Macedonia and of Bulgaria (4,5) statistically significant differences between them were observed in four systems. These findings thus disprove the theories of Slav historians who claim that the inhabitants of Greek Macedonia are Slavs and not Greeks. From the above mentioned papers it can be concluded that the Turks and the Bulgarians are genetically closer to the Mongloids among all the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries. These results support the notion of the origin of the Turks and Bulgarians from Central Asia and distinguish them from the Greeks. Finally, although there has been gene flow from East to West in the Mediterranean area, the inhabitants of Greece are closer to the Italians and French, than to the Turks or to the Bulgarians. Thus, for religious, cultural and linguistic reasons there has been only limited gene flow between Greeks and Turks or Bulgarians.

E. The genetic composition of Greek refugees from Asia Minor.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, some 2.000.000 Greeks were living outside Greece in Asia Minor. The presence of this large Greek population had been established on the West coasts of Asia Minor by 800 BC and spread gradually northward along the Blac Sea coast. These Greek populations maintained their Greek identity throughout the centuries, even under the Ottoman rule. They remained separated from the neighbouring populations by religious and language boundaries. The areas of Pontus and Cappadochia especially were centers of Greek culture. The first world war was followed by the Greek - Turkish war. In 1923 a treaty (Treaty of Lausanne) was signed between Greece and Turkey for the exchange of minorities. Before and after that Treaty a considerable number of Greek Christian refugees from Asia Minor, Pontus, Constantinople and other areas emigrated to Greece. Of these, 700.000 settled in Macedonia and West Thrace. About 25% of the population of Macedonia were, in 1928, of immigrant origin. It is difficult now, more than two generations later, to distinguish the autochthonous and immigrant populations. One of the 1047 communities where refugees were settled was Platy. The village of Platy is situated in the middle of Greek Macedonia in the province of Imathia. The genetic composition of this population was studied by Tills et al (6). Of the 1558 inhabitants in 1973, 1038 donated blood for genetic tests. Blood grouping tests and electrophoretic analysis were performed at the laboratory of Biological Anthropology of the British Museum of Natural History at London in collaboration with the Greek Red Cross. Tests were carried out for ten blood group systems (ABO, MNSs, Rhesus, Pj, Lutheran, Kell, Duffy, Kidd, Wright and Redin), three plasma proteins (Haptoglobin, Transferin and Haemoglobin), and 8 red cell enzymes (ACPH, AK, ADA, EsD, G6PD, PGM, 6-PGD and PHI). The findings from the Platy sample have been compared to those of Greek mainland, Turkey and Bulgaria. When examining a population, such as the Platy population, system by system it is difficult to conclude whether the particular population resembles either the A or the B population. Theoretically, one must simultaneously examine about ten genetic systems. So, the genetic distance was calculated (6) using data for the following 8 genetic systems: ABO, MNSs, Rhesus, Haptoglobin, Acid Phosphatase, 6-phosphoglucomutase dehydrogenase, Adenyulate Kinase and Adenosive deaminase. These were the only systems for which data were available for all four populations. Using the appropriate mathematics, the genetic distances were calculated among the Platy sample, the mainland Greeks, the Turks and the Bulgarians and the obtained results are shown in Fig 2. As can be seen, the differences between the four populations are small, but the Platy sample appears to be slightly closer in its relationship to the Greeks than to the Turks. Furthermore, the refugees of Platy are closer to the Turks, than to the Bulgarians. The incidence of carriers of b-Mediterranean and sickle cell anaemia as well as of the glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency have been investigated in the sample of 410 individuals from Pontus by Sinakos et al (1975) at the 1st Clinic of Pathology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, headed by professor D Valtis. Low frequency of G-6-PD deficiencies (2%) and b-Mediterranean anaemia (3,7%), and only one carrier of the Hb-S variant were found. The distribution of the moderate pthalassaemia was heterogenous and correlated with the topography of malarious areas from where they had immigrated in the past.

F. The genetic composition of Greek Sarakatsans.

The nomadic and primative populations in various parts of the world are experiencing social pressures and changing their lifestyle by settling alongside the urban populations. However, there are still several population groups in Europe which provide an excellent opportunity to study the biological effects of such social changes. In this respect, the endogamic population of Sarakatsans is of great interest. Sarakatsans are nomadic shepherds of continental Greece, who today number about 80.000 in Greece. They live in the mountainous areas of Thessaly, Macedonia, Epirus, Thrace and Sterea Hellas. Their seasonal migrations have led many of them across the border of Bulgaria (15.000), Albania, South Yugoslavia and Turkey. They all speak solely Greek, wherever they live (7,8). Their particular dialect contains trace elements of ancient Greek. They have remained genetically isolated for many centuries, probably due to the mountainous terrain and their culture, pattern of marriage and traditional way of life. But during the last 20 years, they have started to abandon their nomadic way of life and to settle in villages or cities, changing their occupation and marrying outside the group. A process of isolation breakdown is obvious. The genetic study of this group therefore is important. Chatzimichali (9) gave evidence that they are a population group which, in social organization, exemplify certain prototypical elements of Greek culture. In recent years Poulianos (10) using metrical and morphological traits suggested that the Sarakatsans are local upper Paleolithic survivors and may be considered as the most ancient population in Europe. The genetic study of this group therefore is equally important as that of the Basques in Spain and the Lapps in Scandinavia. Blood samples were collected from 232 unrelated individuals (11). The studied area comprised the whole area of distribution of Sarakatsans in Greece. Part of the investigation was carried out at the Department of Genetics, Development and Molecular Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece and part at the Division of Human Genetics, University of Newcastle Upon Type, UK with the aim of examining their genetic structure and estabishing their affinity to other populations of Europe, A random sample of 232 Greek Sarakatsans has been studied for 10 blood groups, 11 enzymic genetic systems, sickle cell haemoglobin and for colour blindness. The allelic frequencies of the 17 polymorphic loci have been compared with those of other samples from the Greek mainland and other European populations. It seems worthwhile to summarize the results of the comparison between the Sarakatsani population and other Greek samples for the 17 polymorphic genes. In comparison with geographically neighbouring inhabitants, significant differences were detected in 7 out of 28 possible comparisons. In conclusion, the Sarakatsans tend reasonably well to resemble the rest of the Greek population. The comparison with European populations indicates that the Sarakatsans have gene frequencies similar to other Mediterranean and European populations. However, the monomorphism of the Kell system, the low frequency of the GLO*1, AK*1 and ACP*B alleles and the high frequency of the GPT*1, EsD*l and ACP*C alleles, are noteworthy. Furthermore, the Sarakatsans are not a high risk group for G6PD dificiency, HbS and (3-thalassemia (12). The low incidence of G6PD dificiency, abnormal haemoglobin variants and p-thalassaemia heterozypotes may be due to their life in the mountain areas in the past centuries.

G. The genetic structure of Greek Gypsie.

The endogamic and nomadic population of Atzigani, as the Greek Gypsies are called, is estimated to be 25-30.000 individuals, scattered throughout the country. It seems that they left India starting from the Xth through to the Xllth centuries. They landed in Greece at the beginning of the 14th century. They have their own customs and traditions. Bartsocas et al (13) have studied the genetic structure of the Greek Gypsies at the Second Department of Pediatrids at the University of Athens. The investigation was carried out in 200 individuals in five blood group systems (ABO, MN, Rhesus, Kell and Duffy) and two protein systems (haemoglobin and ceruloplasmin). From the obtained results the authors concluded that the ABO, Rhesus, MN and Duffy gene frequencies varied significantly from the figures obtained for the Greek population. However, there seems to be some similarity, especially as concerns the ABO, Rhesus and Duffy blood groups, between the distribution of the gene frequencies of the Greek Gypsies and today's inhabitants in the Punjab region of India and Western Pakistan, the supposed regions of origin of the Gypsies. The above mentioned conclusion was also supported from the results of Sinakos et al (14). The Sinakos et al research was conducted in 557 individuals. Their research indicated a high frequency of G-6-PD dificiency (21,2%) and a considerable one of p-Thalassaemia (8,6%). These high frequencies might be attributed to the fact that they have lived for many centuries in regions where malaria was endemic. Alternatively, the above mentioned hight frequencies of hereditary diseases, as well as the occurence of rare hereditary disorders, could be attributed to the isolation and inbreeding of the Gypsies.

Conclusion

The study of the language of genes provides us with clues about the origin and history of the inhabitants of Greece. The above mentioned results consistently show the great genetic similarity between the inhabitants of Greece and the inhabitants of Italy. Especially the results indicate strong genetic affinities between the inhabitants of Greece and those of southern parts of Italy. On the other hand, there are great genetic distances between the inhabitants of Greece and those of Turkey and even greater between Greeks and Bulgarians. Thus, historical facts are backed by genetical data.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Triantaphyllidis C, Kouvatsi A, Kaplanoglou L. The genetic distances between the inhabitants of nine Mediterranean countries and the three Major Human races. Human Haredity 1983; 33: 137-139.

2. Triantaphyllidis C, Kouvatsi A, Kaplanoglou L, Natsiou T. Genetic relationships among the inhabitants of nine Mediterranean countries. Hum Heredity 1986; 36: 218-221.

3. Piazza A, Cappelo N. Olvetti E, Rendine S. A genetic history of Italy. Am Human Genet 1988; 52: 203-213.

4. Stamatoyannopoulos G, Thomakos A, Giblett ER. Red cell enzyme polymorphisms in the Greek populations. Humangenetik 1975;27:23-30.

5. Kaplanoglou L, Triantaphyllidis C, Genetic polymorphism in a North-Greek population. Hum Hered 1987; 32: 124-129.

6. Tills S, Warlow A, Lord J, Suter D, Kopec AD, Blumberg BS, HesserJE, Economidou I. Genetic Factors in the Population of Platy Greece. Am of physical anthropology 1983;61: 145-156.

7. Hoeg C. Les Saracatsans une tribu nomade grecque. Paris-Copenhage 1926; Vol 1 and 2.

8. Georgakas D. About the origin of Sarakatsans and their name (in Greek). Thrac lang andLaogrTressury 1949; 14: 192-270.

9. Chatzimichali AN. Sarakatsan, Vol 1, Part A and B, Athens (in Greek) 1957:498.

10. Poulianos AM. Sarakatani: The most ancient people in Europe. In Phys Anthrop of European Populations, ed Schwidetzky Mouton Publ. The Haque 1980: 175-182.

11. Kouvatsi A, Papiha S, Peios C, Triantaphyllidis C. Genetic study of blood groups in Greek Sarakatsani. 14th Greek Panh Soc of Biological Sciences. Cyprus 1992.

12. Sinakos Z, Tegos K, Mayropoulos K. Parcharidis G, Hadjigeorgiou-Zambouli D, Korandjis I, Valtis D. Haemotological findings in gypsies. latriki Epitheorisi Enoplon Dynameon (Athinae in Greek) 1974; 8:395-400.

13. Bartsocas CS, Karayani C Tsipouras P, Baibas E, Bouloykos A, Papadatos C, Genetic structure of the Greek Gypsies. Clinical Genetics 1979; 15:5-10.

14. Sinakos Z, Tegos K, Korantzis J, Spiliopoulos A, Valtis D. Haemotological findings in the Sarakatsani tribe (A study of 550 individuals). Arch Med Soc (in Greek) 1975;(Nol): 113-116.

THE GENETIC COMPOSITION OF THE INHABITANTS OF GREECE

Professor of Genetics

School of Biology Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

THESSALONIKI 1993

Introduction to the speech «The genetic composition of the inhabitans of Greece» by Dr Penelope MinasidouMavridou, President of the Medical Women Association of North Greece.

When a few years ago, the French historian Dyrosel wrote in one of his books and commented in interviews that «the Greeks come from the Turks and that the entry of Greece into the European Community was a mistake» we were all deeply enraged by these unfounded and untrue historical remarks. Of course we all, not of the faculty of Biology, did not know that apart from historical data, we could also prove Dyrosel and some other so called friends wrong based on scientific research. We did not know that in the School of Biology of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the Professor of Genetics Mr C. Triantaphyllidis and his associates had a scientific publication about our genetic origin. When we read in the press the article-protest of Dr. C. Triantaphyllidis, which also referred to more publications from foreign Universities dealing with the same subject, like the one of Professor Piazza and associates from the University of Torine, we felt proud of this not only serious, but also valuable publication of our university and we as a Medical Women Association of North Greece, concluded that the results of this scientific research be known to all us Greeks and consequently to the whole world. Every Greek, wheever he may be, is interested in discovering his roots and this not in order to feel more Greek, of this he is certain, but to be able to refute not only historically but also scientifically antihellenic opinions of some people and others who have designs on our Greek heritage. The Medical Women Association of North Greece would like to thank Dr C. Triantaphyllidis who so readily answered our request that this speech be given and that he takes care of the publication of this leaflet which is a summary of the subject «The genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece» written in Greek and English to be sent all over Greece and even all around the world, so that everyone realises how Greek our genealogy is, genetically speaking as well. The Medical Women Association of North Greece owe a big thanks to the President of the Medical Association of Thessaloniki Dr N. Aggelidis, the General Secretary Dr G. Xatzedemos and the board who so eagerly cooperated in the organization of the speech which took place in the Chamber of Commerce on March 3rd 1993 and who were the granters of the capital for the first edition of the leaflet titled « The genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece». We would also like to thank the colleaque Dr C. Stasinopoulos, the Editor of the Journal of Medicine Galinos and Mr Pan. Papageorgiou, Manager Editor of the Journal, for the publication of the speech in the Journal and the republication of the leaflet so that it continues to be sent to all the Libraries of the World and to many Institutions.

The first inhabitants of Greece, the Prohellens, arrived in Greek territory at about 8.000 to 6.000 BC. Later, they developed in Crete and the Greek islands those marvellous civilizations which are known as Minoan and Cycladic. The Hellenes (= Greeks) arrived on the Greek mainland in succesive waves during the end of the Bronze Age (2.500 to 1.000 BC). Their arrival has been establisched through archaelogical excavations, linguistic records and literaly sources. The next three centuries (1.100-800 BC) saw an increase of Greece's population, while Hellenic(=Greek) civilization and culture were advanced. Meanwhile, important colonizing enterprises started, which spread the Hellenes futher afield from the Greek mainland. By the 8th century there were Hellenic settlements in modern Bulgaria and Rumania, on the coasts of the Black sea and of Asia Minor. The Greeks also colonized parts of Sicily and Southern Italy, which came to be known as Magna Graecia (Great Greece) and many points along the French, Spanish and North Africa coasts. This Early colonization was the beginning of a process of Hellenization of the indigenous populations. In the 4th century Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) extended greek colonization and civilization even further, to include much of Egypt and the Middle East and to reach even India. Colonization and hellenization continued for more than two hundred years and was maintained during the Roman imperial rule. During the Byzantine period Anatolia, with the major city in the interior of Cappadochia, was one of the most important regions with a Greek population outside of Greece itself. The study of the inhabitants of Hellas (= Greece) is usually based on historical, linguistic and archaeological records. This article aims to investigate the same subject from a different angle, since it is based on Biomediqal - genetical - data. It is worth mentioning that it was in Greece that the first study of blood group frequencies was ever made. It was carried out by Professor and Mrs Hirszfeld (1919) when they were working in Salonika during the First World War and had the opportunity of studying large numbers of soldiers frome different countries. Five hundred Greeks were included in their samples. Since then, and up to the present day, a number of investigators, mostly greeks, have studied the frequency of alleles of genes that code for blood groups, enzyme and protein polymorphisms, among the Greek people. Several authors have studied local or isolated Greek populations. This aricle is an attempt to present the genetic structure of the inhabitants of modern Greece, as well as the genetic composition of isolated Greek populations for which enough genetical data are available. These populations are the refugees from Asia Minor, the endogamic and nomadic populations of Sarakatsans and the Gypsies. The history of a language - its evolution - can be traced from the simiiiarities and differences of living languages and their literaly fossils. Such linguistic evidence can be used to trace the history and relationships of populations. In the same way, shared genes can be used to trace patterns of genetic relationships among human populations. Because of the above mentioned immigration of Greeks all over the Mediterranean region, it seems interesting to investigate the genetic relationships between the inhabitants of Greece and the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries as well as between the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries and the three major human reces*. Previously, the genetic relationships between the human populations were studied mainly by using morphological characters. In recent years, however, blood groups and other protein and enzyme polymorphism (1976) have been studied in human populations. The study of blood groups and other genetic polymorphisms for this type of work is more attractive from, say craniometric data, because of two reasons: their lack of environmental lability and their simple genetic determination. Today, for the same purpose, the scientists are studying the polymorphism of the mitochondrial and nuclear genetic meterial (DNA), as well as the differences in the order of nucleotides of particular segments of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.

* The data from population genetic studies support the notion that there are no human races, but only human populations. So, the term race, in this article, is used only for the convenience of presentation of the results.

A. The genetic relationship between the inhabitants of Greece and the inhabitants of other Mediterranean countries.

The Mediterranean region is divided into many countries. The population of this area is quite diverse consisting of people of different nationality, language and religion. Hence, it is worthwhile to determine the genetic relationships among the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries as well as the genetic distances between the inhabitants of 9 Mediterranean countries and the 3 major human races. For that purpose data on at least 16 genetic loci from nine Mediterranean countries were used (1,2). The genetic markers that were included were blood groups, ie ABO, MNSs, Rhesus, etc, protein loci: ACPH, AK, Hp, etc, from the following countries: France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Libya, Israel, Egypt, Algeria. We also decided to include Bulgaria in the study. The majority of the data for Caucasoids and Mongoloids were taken from US Caucasians and from Japanese, respectively. The data for Negroids were taken from Africans as well as from African Americans. Using the above mentioned data the genetic distances among the inhabitants of the nine Mediterranean countries were computed. Using these estimates, a dendrogram (Fig 1) has been constructed. The smallest genetic distances (or the greater genetic similarity) occur between French - Spaniards, Greeks - Italians, French - Italians and French - Greeks, whereas the greatest distances are between the Algerians and the inhabitants of the other Mediterranean countries. The populations of the North Mediterranean countries were clustered together, whereas this was not the case for South Mediterraneans. Thus one can conclude that the genetic distance of the inhabitants of Greece from the populations of other countries decreases in the following order: Italy, France and then Turkey. These findings therefore strongly contradict the suggestion of the French historian Z Dyrozel that the Greeks are descentants of Turks.

B. The genetic distances between the inhabitants of nine Mediterranean countries and the three major human races.

Anthropologically, the Mediterraneans belong to the Caucasoid group, although some Negroid and Mongoloig admixtures have to be taken into account. The genetic analysis demonstrates certain features of interest.

1. The genetic distance of the populations of North Mediterranean countries from Caucasoids decreases

from the East to the West.

2. The genetic distance from Mongoloids increases from the East to the West for the populations of North and South Mediterranean countries.

3. The genetic distances between Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Italians, Spaniards, French, Israelis and Caucasians are smaller than that between the inhabitants of each country and the Negroids.

4. Libyans and Egyptians are closer to Negroids than to Mongoloids and Algerians are closer to Negroids than to Caucasoids. This is probably caused by Negroid immigration into these countries.

C. Comparison between the genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece and Italy.

Our results show, that the inhabitants of Greece and Italy are genetically very close. It is worth mentioning that Professor A Piazza et al (3) of the Dipartimento of Genetica of the University of Torino has reached the same conclusion. For the reconstruction of the genetic history of the inhabitants of Italy his Laboratory has used many genetic loci (blood groups and protein polymorphisms), as well as historic and linguistic records. By 400 BC the population of Italy was about 4 million people. The Greek colonies of Sicily alone accounted for 1,5 million .people, of which more than 10% (about 200.000) were of Greek origin. To these Greek inhabitants of Sicily another 100.000 Greek colonizers in the Italian peninsula, may be added so that before the Roman period, one in every 10-13 inhabitants of Italy was Greek. Even if these numbers must be taken with caution, their order of magnitude might give an explanation for the remarkable differentation of Magna Greacia (South Italy and Sicily) from the rest of the Italian mainland, as well as for the great genetic similarity of the Italian southern regions with the inhabitants of modern Greece. The loci used for such studies are mainly polymorphic. Thus, the calculated genetic distances tend to be an overestimate. Keeping this fact in mind, one can estimate the time since divergence between the Greeks, the Italians, the French and the Spaniards. These populations appear to have diverged from the Caucasoid line about 8.000 years ago or in the mesolithic period. This rough estimate based on evidence of molecular evolution aggrees quite well with suggestions based on anthropometric measurements and archaeological evidence that North Mediterranean populations migrated from a common root in Central Europe.

D. Comparison between the genetic composition of the inhabitants of Greece and Bulgaria.

The genetic polymorphisms have been studied in only one other Balkan population, that of Bulgaria. Historically, the two populations differ considerably. The Greeks migrated to Southeastern Europe at about 1500 to 1100 BC. The Bulgarians, a Mongolic tribe migrated to what is today Bulgaria during the 8th century AD. There they were absorbed by local Slav populations. The estimated genetic distances between the inhabitants of Bulgaria and the four Mediterranean countries studied (Turkey, Greece, Italy and France) indicate that: The genetic composition of the inhabitants of Bulgaria is closer to that of the inhabitants first of Italy, next of Turkey, and then France, whereas the greatest genetic distance was found between the inhabitants of Greece and Bulgaria. The gene frequencies of five polymorphic systems (AK, PGM, ADA, ACPH, 6-PGD) in the Greek and Bulgarian populations were compared in 1975, by Stamatoyannopoulos et al (4) of the Division of Medical Genetics, University of Washington Seattle, USA. Only one system, AK, has similar frequencies. Thus, among the polymorphic systems so far compared, statistically significant differences were observed in four systems. Therefore, the distribution pattern of the gene frequencies differs considerably between the two populations. Furthermore, the pattern of gene frequencies in the Bulgarian population resembles to that of Asiatic populations. The existing data also sheds some light on the debate between Greek and Slavic historians regarding the ethnic origin of the population inhabiting Greek Macedonia. On the gene grequencies of seven polymorphic systems (AK, PGM, ADA, ACPH, 6-PGD, Hp and ABO) studied in the inhabitants of Greek Macedonia and of Bulgaria (4,5) statistically significant differences between them were observed in four systems. These findings thus disprove the theories of Slav historians who claim that the inhabitants of Greek Macedonia are Slavs and not Greeks. From the above mentioned papers it can be concluded that the Turks and the Bulgarians are genetically closer to the Mongloids among all the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries. These results support the notion of the origin of the Turks and Bulgarians from Central Asia and distinguish them from the Greeks. Finally, although there has been gene flow from East to West in the Mediterranean area, the inhabitants of Greece are closer to the Italians and French, than to the Turks or to the Bulgarians. Thus, for religious, cultural and linguistic reasons there has been only limited gene flow between Greeks and Turks or Bulgarians.

E. The genetic composition of Greek refugees from Asia Minor.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, some 2.000.000 Greeks were living outside Greece in Asia Minor. The presence of this large Greek population had been established on the West coasts of Asia Minor by 800 BC and spread gradually northward along the Blac Sea coast. These Greek populations maintained their Greek identity throughout the centuries, even under the Ottoman rule. They remained separated from the neighbouring populations by religious and language boundaries. The areas of Pontus and Cappadochia especially were centers of Greek culture. The first world war was followed by the Greek - Turkish war. In 1923 a treaty (Treaty of Lausanne) was signed between Greece and Turkey for the exchange of minorities. Before and after that Treaty a considerable number of Greek Christian refugees from Asia Minor, Pontus, Constantinople and other areas emigrated to Greece. Of these, 700.000 settled in Macedonia and West Thrace. About 25% of the population of Macedonia were, in 1928, of immigrant origin. It is difficult now, more than two generations later, to distinguish the autochthonous and immigrant populations. One of the 1047 communities where refugees were settled was Platy. The village of Platy is situated in the middle of Greek Macedonia in the province of Imathia. The genetic composition of this population was studied by Tills et al (6). Of the 1558 inhabitants in 1973, 1038 donated blood for genetic tests. Blood grouping tests and electrophoretic analysis were performed at the laboratory of Biological Anthropology of the British Museum of Natural History at London in collaboration with the Greek Red Cross. Tests were carried out for ten blood group systems (ABO, MNSs, Rhesus, Pj, Lutheran, Kell, Duffy, Kidd, Wright and Redin), three plasma proteins (Haptoglobin, Transferin and Haemoglobin), and 8 red cell enzymes (ACPH, AK, ADA, EsD, G6PD, PGM, 6-PGD and PHI). The findings from the Platy sample have been compared to those of Greek mainland, Turkey and Bulgaria. When examining a population, such as the Platy population, system by system it is difficult to conclude whether the particular population resembles either the A or the B population. Theoretically, one must simultaneously examine about ten genetic systems. So, the genetic distance was calculated (6) using data for the following 8 genetic systems: ABO, MNSs, Rhesus, Haptoglobin, Acid Phosphatase, 6-phosphoglucomutase dehydrogenase, Adenyulate Kinase and Adenosive deaminase. These were the only systems for which data were available for all four populations. Using the appropriate mathematics, the genetic distances were calculated among the Platy sample, the mainland Greeks, the Turks and the Bulgarians and the obtained results are shown in Fig 2. As can be seen, the differences between the four populations are small, but the Platy sample appears to be slightly closer in its relationship to the Greeks than to the Turks. Furthermore, the refugees of Platy are closer to the Turks, than to the Bulgarians. The incidence of carriers of b-Mediterranean and sickle cell anaemia as well as of the glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency have been investigated in the sample of 410 individuals from Pontus by Sinakos et al (1975) at the 1st Clinic of Pathology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, headed by professor D Valtis. Low frequency of G-6-PD deficiencies (2%) and b-Mediterranean anaemia (3,7%), and only one carrier of the Hb-S variant were found. The distribution of the moderate pthalassaemia was heterogenous and correlated with the topography of malarious areas from where they had immigrated in the past.

F. The genetic composition of Greek Sarakatsans.

The nomadic and primative populations in various parts of the world are experiencing social pressures and changing their lifestyle by settling alongside the urban populations. However, there are still several population groups in Europe which provide an excellent opportunity to study the biological effects of such social changes. In this respect, the endogamic population of Sarakatsans is of great interest. Sarakatsans are nomadic shepherds of continental Greece, who today number about 80.000 in Greece. They live in the mountainous areas of Thessaly, Macedonia, Epirus, Thrace and Sterea Hellas. Their seasonal migrations have led many of them across the border of Bulgaria (15.000), Albania, South Yugoslavia and Turkey. They all speak solely Greek, wherever they live (7,8). Their particular dialect contains trace elements of ancient Greek. They have remained genetically isolated for many centuries, probably due to the mountainous terrain and their culture, pattern of marriage and traditional way of life. But during the last 20 years, they have started to abandon their nomadic way of life and to settle in villages or cities, changing their occupation and marrying outside the group. A process of isolation breakdown is obvious. The genetic study of this group therefore is important. Chatzimichali (9) gave evidence that they are a population group which, in social organization, exemplify certain prototypical elements of Greek culture. In recent years Poulianos (10) using metrical and morphological traits suggested that the Sarakatsans are local upper Paleolithic survivors and may be considered as the most ancient population in Europe. The genetic study of this group therefore is equally important as that of the Basques in Spain and the Lapps in Scandinavia. Blood samples were collected from 232 unrelated individuals (11). The studied area comprised the whole area of distribution of Sarakatsans in Greece. Part of the investigation was carried out at the Department of Genetics, Development and Molecular Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece and part at the Division of Human Genetics, University of Newcastle Upon Type, UK with the aim of examining their genetic structure and estabishing their affinity to other populations of Europe, A random sample of 232 Greek Sarakatsans has been studied for 10 blood groups, 11 enzymic genetic systems, sickle cell haemoglobin and for colour blindness. The allelic frequencies of the 17 polymorphic loci have been compared with those of other samples from the Greek mainland and other European populations. It seems worthwhile to summarize the results of the comparison between the Sarakatsani population and other Greek samples for the 17 polymorphic genes. In comparison with geographically neighbouring inhabitants, significant differences were detected in 7 out of 28 possible comparisons. In conclusion, the Sarakatsans tend reasonably well to resemble the rest of the Greek population. The comparison with European populations indicates that the Sarakatsans have gene frequencies similar to other Mediterranean and European populations. However, the monomorphism of the Kell system, the low frequency of the GLO*1, AK*1 and ACP*B alleles and the high frequency of the GPT*1, EsD*l and ACP*C alleles, are noteworthy. Furthermore, the Sarakatsans are not a high risk group for G6PD dificiency, HbS and (3-thalassemia (12). The low incidence of G6PD dificiency, abnormal haemoglobin variants and p-thalassaemia heterozypotes may be due to their life in the mountain areas in the past centuries.

G. The genetic structure of Greek Gypsie.

The endogamic and nomadic population of Atzigani, as the Greek Gypsies are called, is estimated to be 25-30.000 individuals, scattered throughout the country. It seems that they left India starting from the Xth through to the Xllth centuries. They landed in Greece at the beginning of the 14th century. They have their own customs and traditions. Bartsocas et al (13) have studied the genetic structure of the Greek Gypsies at the Second Department of Pediatrids at the University of Athens. The investigation was carried out in 200 individuals in five blood group systems (ABO, MN, Rhesus, Kell and Duffy) and two protein systems (haemoglobin and ceruloplasmin). From the obtained results the authors concluded that the ABO, Rhesus, MN and Duffy gene frequencies varied significantly from the figures obtained for the Greek population. However, there seems to be some similarity, especially as concerns the ABO, Rhesus and Duffy blood groups, between the distribution of the gene frequencies of the Greek Gypsies and today's inhabitants in the Punjab region of India and Western Pakistan, the supposed regions of origin of the Gypsies. The above mentioned conclusion was also supported from the results of Sinakos et al (14). The Sinakos et al research was conducted in 557 individuals. Their research indicated a high frequency of G-6-PD dificiency (21,2%) and a considerable one of p-Thalassaemia (8,6%). These high frequencies might be attributed to the fact that they have lived for many centuries in regions where malaria was endemic. Alternatively, the above mentioned hight frequencies of hereditary diseases, as well as the occurence of rare hereditary disorders, could be attributed to the isolation and inbreeding of the Gypsies.

Conclusion

The study of the language of genes provides us with clues about the origin and history of the inhabitants of Greece. The above mentioned results consistently show the great genetic similarity between the inhabitants of Greece and the inhabitants of Italy. Especially the results indicate strong genetic affinities between the inhabitants of Greece and those of southern parts of Italy. On the other hand, there are great genetic distances between the inhabitants of Greece and those of Turkey and even greater between Greeks and Bulgarians. Thus, historical facts are backed by genetical data.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Triantaphyllidis C, Kouvatsi A, Kaplanoglou L. The genetic distances between the inhabitants of nine Mediterranean countries and the three Major Human races. Human Haredity 1983; 33: 137-139.

2. Triantaphyllidis C, Kouvatsi A, Kaplanoglou L, Natsiou T. Genetic relationships among the inhabitants of nine Mediterranean countries. Hum Heredity 1986; 36: 218-221.

3. Piazza A, Cappelo N. Olvetti E, Rendine S. A genetic history of Italy. Am Human Genet 1988; 52: 203-213.

4. Stamatoyannopoulos G, Thomakos A, Giblett ER. Red cell enzyme polymorphisms in the Greek populations. Humangenetik 1975;27:23-30.

5. Kaplanoglou L, Triantaphyllidis C, Genetic polymorphism in a North-Greek population. Hum Hered 1987; 32: 124-129.

6. Tills S, Warlow A, Lord J, Suter D, Kopec AD, Blumberg BS, HesserJE, Economidou I. Genetic Factors in the Population of Platy Greece. Am of physical anthropology 1983;61: 145-156.

7. Hoeg C. Les Saracatsans une tribu nomade grecque. Paris-Copenhage 1926; Vol 1 and 2.

8. Georgakas D. About the origin of Sarakatsans and their name (in Greek). Thrac lang andLaogrTressury 1949; 14: 192-270.

9. Chatzimichali AN. Sarakatsan, Vol 1, Part A and B, Athens (in Greek) 1957:498.

10. Poulianos AM. Sarakatani: The most ancient people in Europe. In Phys Anthrop of European Populations, ed Schwidetzky Mouton Publ. The Haque 1980: 175-182.

11. Kouvatsi A, Papiha S, Peios C, Triantaphyllidis C. Genetic study of blood groups in Greek Sarakatsani. 14th Greek Panh Soc of Biological Sciences. Cyprus 1992.

12. Sinakos Z, Tegos K, Mayropoulos K. Parcharidis G, Hadjigeorgiou-Zambouli D, Korandjis I, Valtis D. Haemotological findings in gypsies. latriki Epitheorisi Enoplon Dynameon (Athinae in Greek) 1974; 8:395-400.

13. Bartsocas CS, Karayani C Tsipouras P, Baibas E, Bouloykos A, Papadatos C, Genetic structure of the Greek Gypsies. Clinical Genetics 1979; 15:5-10.

14. Sinakos Z, Tegos K, Korantzis J, Spiliopoulos A, Valtis D. Haemotological findings in the Sarakatsani tribe (A study of 550 individuals). Arch Med Soc (in Greek) 1975;(Nol): 113-116.

THE GENETIC COMPOSITION OF THE INHABITANTS OF GREECE